Of mud and mangroves

Through necessity, the early settlers viewed the Australian landscape through an economic lens, assessing the natural value of the land in terms of what they could extract from it.

Now, as we shift our focus to natural capital – the air, water, soil, plants and animals that essentially keep us alive – we are beginning to value more diverse landscapes. But not all get the attention they deserve.

A case in point are the muddy, mucky landscapes known as coastal saltmarsh. Despite providing an astonishing array of ecosystem services, they remain greatly undervalued. But why?

Blue carbon landscapes

Broadly defined as a mosaic of coastal ecosystems, saltmarsh is one of the most productive ecosystems on Earth, likened to kidneys or lungs in terms of its ability to filter pollution and intercept nitrogen run-off from farms.

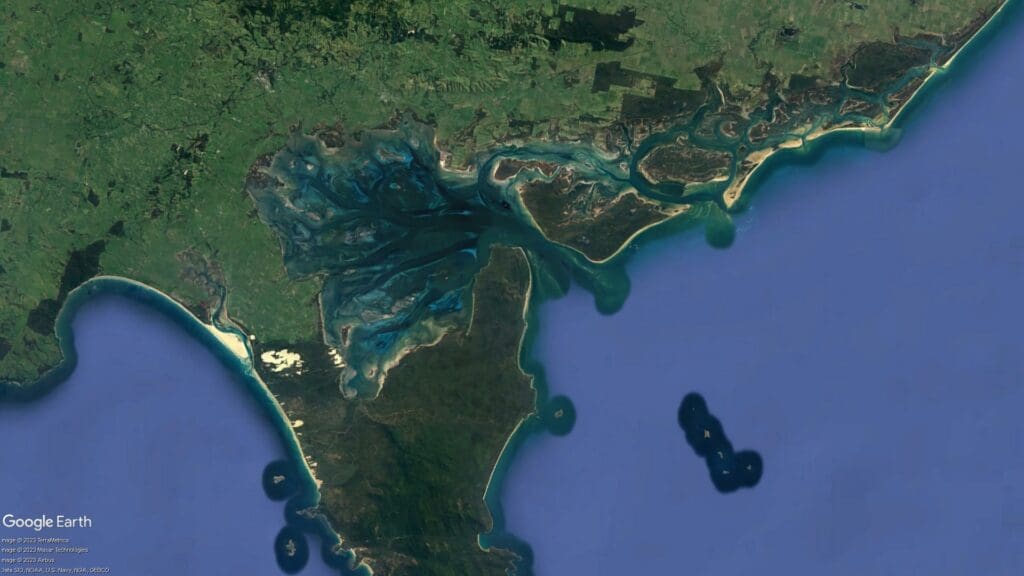

In South Gippsland, Victoria, this lung effect can be seen from above as we look down at the 67,186-hectare site of Corner Inlet. Adjacent to Wilsons Promontory and the Nooramunga Marine and Coastal Park, Corner Inlet is one of 64 wetland areas listed as a Wetland of International Importance under Ramsar Convention.

Fringing the Inlet and the 40 plus sandy barrier islands within the inlet are some of the most floristically diverse coastal saltmarshes in the country; marshes that not only reduce farm run-off and provide a nursery for young fish, but capture and store carbon at rates 30-50 times higher than the equivalent area of soil in terrestrial forests – a process known as blue carbon.

Reframing notions of value

According to Melbourne University wetland ecologist, Paul L. Boon, Australians have always undervalued saltmarsh. He uses the folktale of Cinderella to describe how they are perceived as the ugly or poor stepsister of inland wetlands – wastelands standing between us and our desire to live on the coast and extract resources from it.

Viewed through European eyes, saltmarshes certainly ain’t pretty; in Cinderella’s words, “When they look at me, they see a mess”.

But if you look closer you can see the jewels in the landscape, like the samphire or glasswort whose jointed branches look like strings of coloured beads. Or the red seablite that mixes with the samphire to create rivers of red marsh.

A population at risk

While Corner Inlet retains 80% of its saltmarshes, a salutary lesson can be learned if we look west to Anderson Inlet, where 60% of the marshes have been lost. Or further north to Botany Bay – ironically named for its biodiversity – where losses in some areas are reported as 100%.

However, some plants within the Corner Inlet, including the iconic grey or white mangrove, are endangered. Perversely, if the saltmarshes are not managed well, the system gets out of balance and mangroves take over. So these systems need to be managed carefully.

An island of hope

In 2022, leading Victorian botanists Tim D’Ombrain and Karl Just got wind of a potential sale of Little Dog Island off the coast of Hedley within Corner Inlet.

Formerly owned by a group of developers who attempted to build an eco-resort on the island – complete with 9-hole golf course – the 62-hectare island was abandoned when the project failed. It lay idle for 14 years until Tim and Karl invited Federation University paleoecologist Professor Peter Gell, Rendere Environmental Trust Strategic Director Jim Phillipson and Carbon Landscapes co-director Dr Steve Enticott to collaborate on a new conservation project.

Together they formed a not-for-profit organisation called Nooramunga Land & Sea to hold the island in trust for future generations with provisions to enable community engagement and collective land stewardship.

The ‘saltmarsh crew’ are now repairing damage caused by the development and eradicating feral animals and weeds. They’re also investigating opportunities to secure other private properties in the area.

“We see these landscapes as ecological gems in the jewel that is Corner Inlet,” says Jim Phillipson. “They are beautiful and highly productive landscapes that support human health and wellbeing. But they are fragile and easy to disrupt. To protect them, we need to value them and promote their intrinsic value – just by being left alone.”

Like other areas within the Inlet, Little Dog Island attracts a wide range of migratory birds. It may also provide habitat for the critically endangered Orange-bellied Parrot, which feeds on plants that grow in salty or alkaline conditions, such as saltmarshes.

Expectations are high that the Parrot will be spotted on Little Dog Island, with members of the conservation crew participating in BirdLife Australia’s Winter Surveys. The crew are also exploring opportunities to secure other properties in the Inlet to build biolinks and connections for plants, animals and people.

*Story and most photos by Robyn Gower. Story Published in Wildlife Australia magazine, Spring 2023.

With thanks to Professor Paul Boon, whose research on saltmarsh is published in the CSIRO journal Marine & Freshwater Research and Royal Botanic Garden Sydney journal, Cunninghami